There are so many current and upcoming regulations regarding the restriction of PFAS on EU level that they have started to overlap. But that’s a good thing, right – the more bans on harmful “forever chemicals” the better? Actually, legislative overlap risks causing confusion and double-work, potentially creating loopholes rather than stricter regulation.

Chemicals have – and largely continue to be – regulated one substance at a time. This is of course a slow and cumbersome process, especially when it comes to large chemical “families” like PFAS. However, steps are now being taken towards banning groups of chemicals with similar structure and properties collectively, which is of course a huge leap in the right direction.

PFAS is a group of around 5,000 man-made chemicals, consisting of highly fluorinated carbon molecules of various sizes. All PFAS have similar toxic characteristics: carcinogenic, endocrine-disrupting, and immunosuppressive, as well as being – the icing on this awful layer cake – mobile or bio-accumulative, and extremely persistent, hence the nickname “forever chemicals”.

The toxics that have taken more than 50 years to restrict

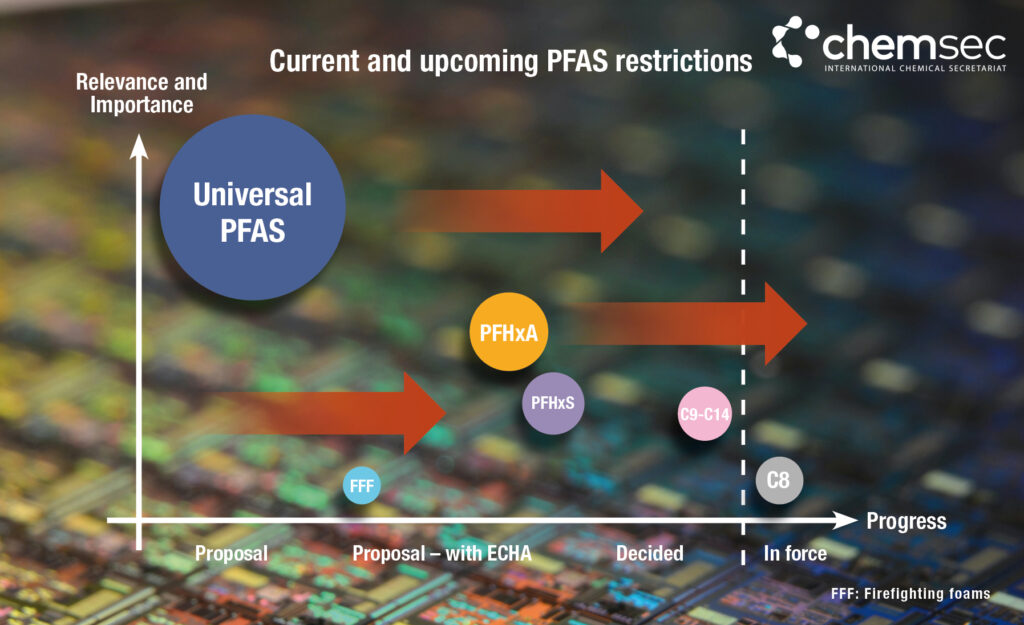

Although PFAS chemicals have been commercially produced since the 1950s, and their harmful properties have been known for decades, so far only a few of them are regulated at EU level. The first regulations came into force in 2006 and 2017 respectively, mainly targeting the PFAS chemicals PFOS and PFOA, commonly used in textiles, carpeting, paper, and – of course – teflon production.

PFOS and PFOA are both C8 chemicals, meaning the molecule structure contains eight carbon atoms. PFAS chemicals that degrade into PFOS and PFOA, or are otherwise “related” to the two chemicals, are also covered by the regulations. However, authorities still have not provided an official list of exactly which these “related substances” are.

Next up for restriction were PFAS with between 9 and 14 carbon atoms in their molecular structure (C9-C14), as well as PFAS that degrade into these chemicals. These kinds of substances are often used in textiles, carpets, paint, and paper.

The C9-C14 restriction is decided and will come into force in February of next year. The “proper” names of these substances are long and tongue-twisting, for example Heptacosafluorotetradecanoic acid, which makes it easier to name them after their number of carbons. In this restriction case, an indicative but not complete list of substances was provided.

“By now, legislators were on a roll, so why stop there?”

By now, legislators were on a roll, so why stop there? PFAS with six carbon atoms have been extensively used and, in many cases, the go-to solution when moving away from the C8 chemistry. C6 PFAS are applied to a variety of products, including firefighting foams, textiles, food contact materials, cosmetics, and semiconductors.

But surprise, surprise – the C6 substances have turned out to be just as hazardous as the C8 ones, leading to a plethora of so-called regrettable substitution, which is when you swap one harmful chemical for an equally problematic one. So now, the C6 substances are subject to proposals called the PFHxA and PFHxS restrictions. As in previous PFAS restrictions, chemicals that degrade into C6 substances are included, and an indicative list of substances has been provided.

Where it gets a bit messy

Up until this point, there is no overlap between the different regulations, as they are based on chemical structure – the length of the main carbon chain. Even if there have been challenges when it comes to determining which PFAS substances degrade into which restricted PFAS chemicals, the carbon chain length approach has been successful in simplifying different regulation initiatives.

“These countries have started working on a universal PFAS restriction proposal, targeting all PFAS for all uses”

However, recent legislative initiatives regarding PFAS have taken a different approach. One proposed restriction initiated by the European Commission, on PFAS in firefighting foams, focuses on a specific use instead of molecular structure.

The restriction proposal covers all PFAS substances used in firefighting foams, regardless of their number of carbon atoms, or any other means of structural identification.

In addition, five EU member states – Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Denmark, and Sweden – have taken everything one step further. These countries have started working on a universal PFAS restriction proposal, targeting all PFAS for all uses, or as it says in the proposal: “Restriction on manufacture, placing on the market, and use of PFAS.”

The road to confusion is paved with good intentions

It’s important to stress that these initiatives are extremely well intended; PFAS needs to be restricted. The evidence of their hazardous properties is abundant, and as stated in the Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability, there is a need to regulate them – preferably as a group. Wide and effective PFAS bans should be our highest priority!

However, with some of these new proposals, legislation has moved away from the chemical structure approach, and introduced a potential for overlap between the different legislative pieces.

“There are consequences to using different restriction approaches”

Is this really a problem, though? We are regulating hazardous chemicals – that’s great! Well, at first glance it seems like a good idea to “cover all the bases”, but there are consequences to using different restriction approaches.

Once more – from the top!

For example, almost all PFAS used in firefighting foams are C6 substances. A conservative estimate is that at least 95 percent of the PFAS used in firefighting foams are covered by the C6 restriction. That restriction is further ahead; ECHA (European Chemicals Agency) have already done consultations and the SEAC (ECHA’s Socio-Economic Analysis Committee) and RAC (ECHA’s Risk Assessment Committee) have already submitted their opinions, including dates and reasonable transition times.

“Why should ECHA, and everyone else involved in these processes, spend time on doing things again?”

Now, a similar process will have to be done again for the firefighting foam proposal, featuring similar arguments, and opening up for new derogations as well as exemption demands from industry and lobbyists.

Why should ECHA, and everyone else involved in these processes, spend time on doing things again? Time is a resource that should be spent wisely!

One might also wonder about the reason for introducing the firefighting foam restriction proposal. While the ambition to rid all firefighting foams of PFAS is of course commendable – along with all other initiatives aiming to ban PFAS – why single out one specific use, when there is the option of relying on the C6 restriction to handle the issue?

Let’s focus on “the big one”

The goal is clear: PFAS needs to be restricted. The best opportunity to do this in a comprehensive way is through the universal PFAS restriction, which aims to restrict this entire “family” of hazardous substances. This opportunity must not be squandered!

With all these different PFAS initiatives around, it’s important to make sure that the resources are utilized in an efficient way. Less relevant restrictions, such as the firefighting foams restriction, should not be allowed to require valuable resources and hours at the expense of the universal PFAS restriction.

In short, we need the EU to focus on the universal PFAS restriction, which needs to be:

- Strict – exemptions should be kept to the bare minimum

- Comprehensive – all PFAS, all uses

- The PFAS ban to end all PFAS bans – the only regulation we need to put an end to the use of these harmful “forever chemicals”